A while back, I was at a church service and at one point the worship leader read the words of Jesus from Matthew 22:

“‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.’ This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’ All the Law and the Prophets hang on these two commandments.”

After quoting the passage, he went on to say that the entire Bible could be boiled down to these verses.

Several people uttered “amen” and although I agreed wholeheartedly, on the inside, I felt my heart sink a little as I thought “If only…”

If only we truly believed that.

If only we lived as though the Bible really could be boiled down to these few verses.

If only these two commands could be the barometer not only for how we express our faith, but how we define it.

If only we could consider that part of the power and supreme importance of these commands lie in the fact that they transcend doctrine and denomination and religion altogether.

If only we could consider how this teaching may have affected those who initially heard it.

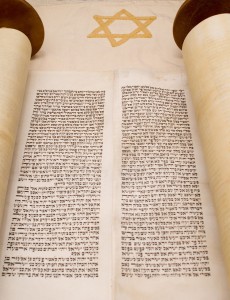

Humor me while we think about that last one for a minute. Let’s say I happened to be present when Jesus spoke these words and I was captured as I considered the intensity of a teaching that claimed that all of the law and the prophets – in other words, the equivalent at the time of our Bible – could be summed up by these verses. And if I made the radical step to live the rest of my life accordingly, would that have been enough?

Humor me while we think about that last one for a minute. Let’s say I happened to be present when Jesus spoke these words and I was captured as I considered the intensity of a teaching that claimed that all of the law and the prophets – in other words, the equivalent at the time of our Bible – could be summed up by these verses. And if I made the radical step to live the rest of my life accordingly, would that have been enough?

Even if I never heard another thing about Jesus – how or why he ultimately died, or whether he was thought to be just a rabbi, or a messiah, or somehow divine. I’m not sure how likely such a scenario would be, but it’s not out of the question to consider it and then go on to ponder, “Would that have been enough?”

According to Jesus, it would’ve been, especially if we consider that the gospel of Luke places these commandments in the context of how to inherit eternal life. Jesus responds, “Do this and you will live.”

If it was good enough for the people following Jesus then, is it not good enough for us now?

It’s hard to know what kind of widespread impact such a teaching had on those who heard it, but it must’ve had an impact on at least some the early followers of Jesus. In a previous post, I talked briefly about the Didache, a church handbook that likely dates to the first century and that gives us a compelling look at the teachings and practices of some of the earliest Jesus followers.

Interestingly enough, the Didache calls out “the way of life” and “the way of death.” The way of life begins by loving God, loving your neighbor as yourself, and not doing to others what you would not want done to you. Ironically, for these Jesus followers, the ways of life and death had nothing to do with orthodox beliefs or doctrines. Things were much simpler hundreds of years before a Bible was canonized and creeds were formulated.

But here we are 2,000 years later. And as nice it sounds to sum the Bible up with the two greatest commands as identified by Jesus, it simply doesn’t work for us. It’s as though we have to define what it means to love God properly, and, in doing so, we create the very structures and doctrines and systems of belief that love is supposed to transcend; indeed, that love has the power to completely obliterate… if we’d allow it to. But instead, we effectively create a whole new version of “the law and prophets,” perhaps because we don’t believe that everything will be just fine if only we’d love God and love our neighbors as ourselves.

This is all particularly relevant in my life right now. For whatever reason, God has brought me beyond the boundaries of the Christian box where I’ve spent most of my life. Of course I didn’t realize I was in a box; I don’t think any of us ever do. And I didn’t set out to venture here, but I’m here, having been pressed to truly engage some hard questions and to probe the status quo of my belief system. And at times it’s been terrifying, largely because where I come from, that’s not okay. (Well, it’s okay as long as you ultimately return to the established answers and beliefs.)

No one wants to mess with the box. I certainly didn’t. And I think it’s because we don’t see it as a box; we see it as ultimate truth.

Frankly, the whole situation just sucks.

It sucks because I’ve invested so much of my life into a church family where there simply isn’t room to grow beyond the established ideas, conclusions, and doctrines (in other words, beyond the boundaries of the box that are defined as truth).

It sucks that even though I’ve invested years and years and years, there’s no possibility that there might be some merit to my evolving views. No possibility that I’ve come to new conclusions responsibly and faithfully.

And it sucks to be backed into a figurative corner and effectively told “It’s not okay to believe those things and it’s even less okay to make those beliefs public. If you want to stick around here, you have to believe X, Y, and Z. These things are non-negotiable.”

And, as if all of that’s not enough, it sucks that now I’m somehow seen as a threat by some because I have “divergent views.”

Divergent views that ironically don’t conflict at all with loving God and loving my neighbor as myself.

Divergent views that couldn’t have even been an issue when Jesus was traipsing around Palestine because they’re only in conflict with doctrines or teachings that developed much later.

But as much as it sucks, I get it.

I understand that, to some extent, there’s an institution that needs to be protected. And I get that people’s faith is in differing places and we need to be sensitive to that, not randomly wreaking havoc on the faith of others.

As one author put it, the challenge is that we end up teaching to the lowest common denominator in order to avoid ruffling the feathers of people in the congregation. It hardly seems fair. Stuff that’s been common knowledge throughout biblical scholarship for centuries doesn’t make it to the average church member (for any number of reasons). And it’s unfortunate, because it has the potential to help our faith grow in amazing ways. And if we engage it responsibly, it doesn’t have to be scary or threatening. It might make us rethink some of our certainties, but history has shown us that that’s usually not a bad thing. It’s just not easy.

In fact, one minister I was talking with fully acknowledged that there may not be anything wrong with these so-called divergent views. If people want to dive into doctrines or some of the deeper topics and they ultimately come to a differing opinion that doesn’t mesh with a traditional view, that’s okay. The problem is, in order for ministers to truly understand these things so they can bring a responsible understanding of them to the congregation, it takes work. A lot of it.

Plus, it can potentially get very messy and uncomfortable, which creates even more work as feathers get ruffled within the congregation. And who wants extra work? As a result, many topics get avoided altogether as staff members opt to keep the message from the pulpit as simple as possible.

Unfortunately, it puts people with said divergent views in a tricky spot, because when differing views haven’t been engaged from the pulpit, they’re seen as threatening. And if word gets out, it can get messy, which means more work for the minister.

And so, the easiest and cleanest way to deal with a situation like this is to say, “It’s not okay to believe these things and it’s even less okay to make these beliefs public. Either toe the party line or leave so as to not disturb anyone else.”

Sigh. Really? Those are the only options, lest I end up being marked as “divisive”?

So here I am on the heels of such a mess, trying to process the conflicting and at times overwhelming emotions that come raging in like a tidal wave.

So here I am on the heels of such a mess, trying to process the conflicting and at times overwhelming emotions that come raging in like a tidal wave.

Anger. Rage. Sorrow. Pain. Confusion.

In some ways, it feels what I imagine a divorce might feel like. An unnecessary divorce, at that.

Plenty of people have pointed out that it’s best this way. It’s best to be in an environment where my path is not only welcomed, but encouraged, perhaps even celebrated. An environment where questions aren’t seen as a threat and where faith is greater than doctrine and tradition.

And many have posed the question of why I’d want to even try to be somewhere that doesn’t allow that.

Yeah, yeah, yeah – I get it. And I agree wholeheartedly. But it still sucks, because the pain isn’t any less real.

And as I try to process it all, I circle back to the words of Jesus.

“‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind’…and… ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’ All the Law and the Prophets hang on these two commandments.”

And I think “If only…”

If only.